Description:

The bristlecone pine has a very limited distribution, usually restricted to the highest elevations of the highest mountain ranges of the Great Basin. It typically is the last tree you see when you start approaching timberline, however sometimes you will see it mixing with whitebark pine in the alpine zone, and very peculiarly it sometimes occurs in unexpected lower elevations. It experiences very cold temperatures (frost can occur any time of the year), as well as very dry conditions.

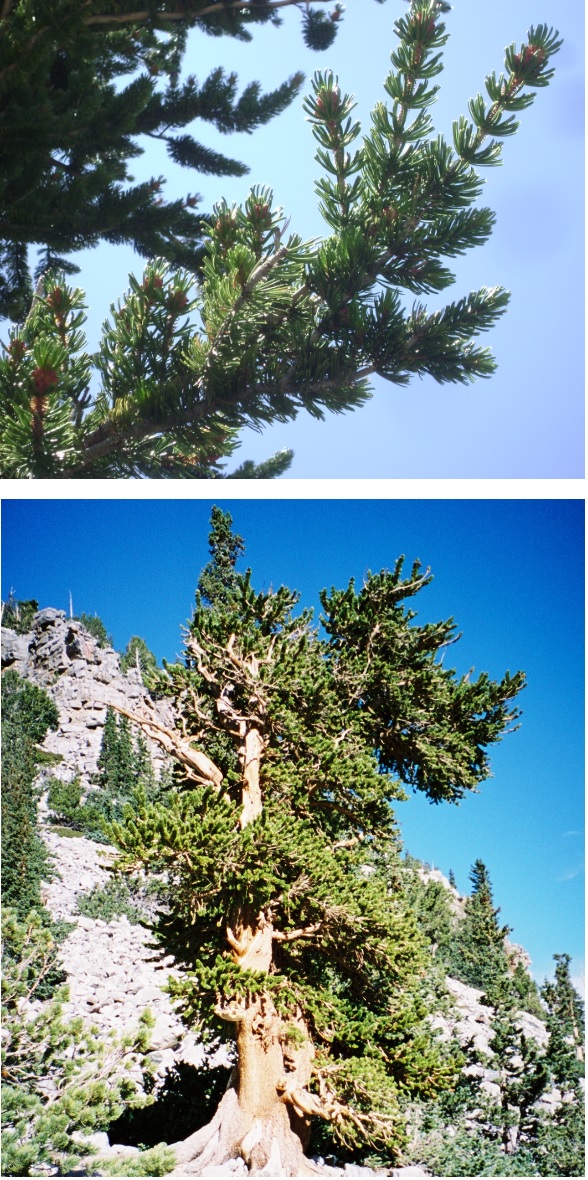

Its shape is quite the antithesis of the symmetrical Christmas tree form of a conifer such as the white fir. It has a gnarled shape that is a testament to its extremely harsh settings. In the older individuals, much of the bark will die, but leave a few strands to sustain the growth of the sparse foliage that survives. In the more favorable areas individuals can grow to about 50 feet tall. And some of them at the lower end of their elevation range can look more “conifer” like and not the gnarled shape of the ones at higher altitudes.

The 2-to-4-inch cones typically hang from the ends of the branches. The needles grow in groups of five, and are tightly arranged in dense clusters.

Perhaps because of the cold, dry climate, or maybe in spite of it, this tree has been considered as the oldest living plant on earth by biologists. Tree cores have revealed that some of the trees are about 5000 years old.

There are two species that were given the name of bristlecone pine. The western ones in California and the Great Basin are Pinus longeava. The ones in the Rocky Mountains are Pinus aristata.

Personal Observations:

In my younger days I backpacked the White Mountains of eastern California. I came across many of them between 10,000 and 12,000 feet. I walked along the Methuselah Trail where some of the oldest specimens are said to be.

While in the Ruby Mountains a decade ago I tried to find the most northern bristlecone pines in Nevada. I found them in the south slope of Lamoille Canyon. There were a few dozen of them, and they seemed to be in pretty good condition. When I compared my findings with David Charlet’s database, they indeed were the most northern individuals officially recorded in Nevada. David Charlet is the leading Nevada biogeographer and has written papers and books documenting the distribution of conifers in the state. The trees I found, although the most northern in the state, were slightly further south than a group of them in Utah.

One of my notable sightings was a bristlecone pine in the Mount Moriah Wilderness Area on the eastern border of the state. On our way out of the wilderness area after a several day trip, Pat, my cousin, spotted a bristlecone pine in an unusual location. We had seen many up higher, but this one was at a very low elevation, in fact, the lowest one ever documented. It was at an elevation of 6220 feet above sea level. It was found near Hendrys Creek. Many times canyons can be much colder than the surrounding hillsides because cold air will flow down into the canyon, and be more similar to the tree’s normal temperature range. That is likely the reason the tree was found far from its normal altitude range. And it was on the eastern side of the mountain range, where it would receive less afternoon heat than the south and west sides.

There is also a sizable population in Great Basin National Park in the very eastern part of the state. The ones I encountered were on the way to a glacier, at about 10,600 feet elevation. (Some call it a “rock” glacier, and not an alpine glacier. However, in the past is was certainly a glacier as substantiated by the obvious moraines down from the feature.)

I spotted one in the Spring Mountains, below Mount Charleston, west of Las Vegas, while on a field trip with David Charlet. It, like the one in Mount Moriah Wilderness Area, was at a fairly low elevation, between 7000 and 8000 feet elevation.