Description:

The Engelmann spruce is one of the largest trees in the high country, sometimes one of the last trees, along with limber or whitebark pine, that you see before you hit the tree line. It likes moist canyons and basins, as well as north slopes. It is a lofty, impressive tree, often forming a lush pyramid-like form. On the other hand, on windy ridges it can be wind-sheared into a low-lying krummholz form. Its small (1-2”) cones lie off the bottom of the branches and have soft, papery scales.

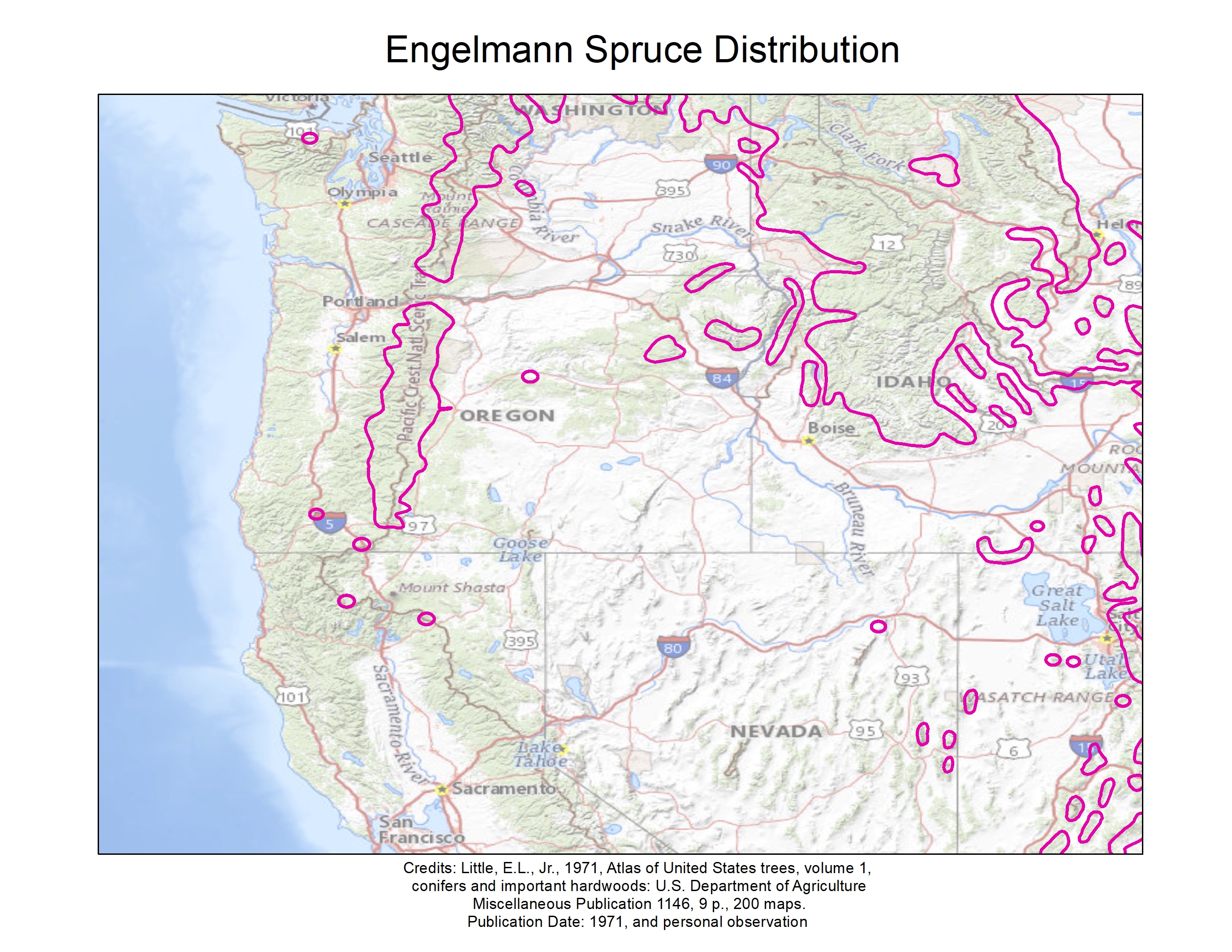

It has a fairly extensive distribution throughout the Cascades and the Rockies, with a few populations in northern California, eastern Nevada, and the Olympic Peninsula. It is definitely an inland tree, not found near the coast like its cousin the Sitka spruce. Because it is often found besides high-country streams, if often provides shade for trout-loving pools.

Personal Observations:

My most substantial effort to find these trees was in the Ruby Mountains of eastern Nevada in 2011. There was reported to be a small population of them in the middle of this large, beautiful mountain range. Some call the heavily glaciated Ruby Mountains, the Swiss Alps of Nevada. The closest of the same species is about a hundred miles to the southeast and several hundred miles to the north and west. I, along with my cousin Pat, hiked three days and many miles of mostly cross-country, rugged territory to get to the remote, disjunct population. The trees had been known to be in the area, but the estimated location was unclear. As it turned out the estimated location turned out to be about a mile away from the actual location, which was in Thorpe Canyon, deep in the heart of the Rubies. We mapped all the spruce along the perimeter of what we perceived the be their boundary and “GPSed” them (meaning we located and logged trees using a GPS unit). There were hundreds of trees within the boundary, both tall ones and many seedlings. I estimated the tallest one to be about 60 feet tall. We scoured the area (in about a mile in all directions) for more of the species, but found none. It rained pretty heavily for two days, with only minor breaks on this September trip. This was pretty consistent with the estimates of some, that the area might receive up to 50 inches of rain a year, which is unusual for Nevada.

According to David Charlet, a biogeographer, it is hard to say whether these trees are a remnant of a larger population that is shrinking due to natural climate change, or they are new immigrants from other mountain ranges

I also found them in Shelvin Park just east of Bend, Oregon at an elevation of 3650 feet, which is somewhat below its typical range. It was outside of all the boundaries of the distribution maps that I came across. This was probably due to both its proximity to the wetness of Tumalo Creek, and the canyon location that tends to hold cooler temperatures (under many meteorological conditions) than the surrounding vicinity.

I was also fortunate to find them in several other beautiful areas. I saw them near Crater Lake when I visited that area in 2019. I also saw them in two areas of eastern Nevada – in Mount Moriah Wilderness Area, and Great Basin National Park. Great Basin National Park is one of the least visited national parks in the country, but well worth the trip to this out-of-the-way place.

My goal is to log them in the Elkhorn Mountains and Wallowa Mountains of eastern Oregon in the near future.